I’m asking the 3O km/h speed limit directly in a fictional conversation today.

Veronika: Hi Thirty, thank you for agreeing to talk to me today. Discussions around you have become more frequent lately, yet they are still quite heated. What do you think it is?

30: Thank you for inviting me. The answer to your question is not easy and I’m sure our whole conversation will revolve around it. The crucial point, however, is that many people are convinced that at higher speeds they can get to a place faster. Common sense leads to this conclusion, if I move faster, I get to my destination sooner. But the truth is that the average cruising speed in the city is around 30 km/h even when the limit is 50. Mainly because we spend a lot of time standing at junctions. I am bringing about a change that is not easy to accept.

Veronika: What do you mean by that?

30: When the speed of the cars drops, the traffic is smoother. Smaller gaps are needed to get into the next lane. There is no need for so many traffic lights or pedestrian controlled crossings. Which brings back the increased flow and reduced downtime while driving that you try to reduce today by stepping on the gas on stretches. The speed of traffic in the city, however, is basically determined by the intersections.

Veronika: You mainly mention cars and traffic flow, but many cities are introducing various measures to reduce car traffic. A lot of people blame you for having something to do with it. How do you see it?

30: I certainly contribute to sustainable transport, but not by limiting cars. As I said before, I am contributing to more fluidity and shorter journey times. But by keeping cars from reaching higher speeds, I’m also making the streets more friendly to cyclists, who normally travel at 15-20 km/h. I make their speed and the speed of cars closer together and it doesn’t create as many dangerous situations. Both groups are more easily tolerated in a shared space.

Veronika: What about pedestrians, shouldn’t they be the most important thing in the city?

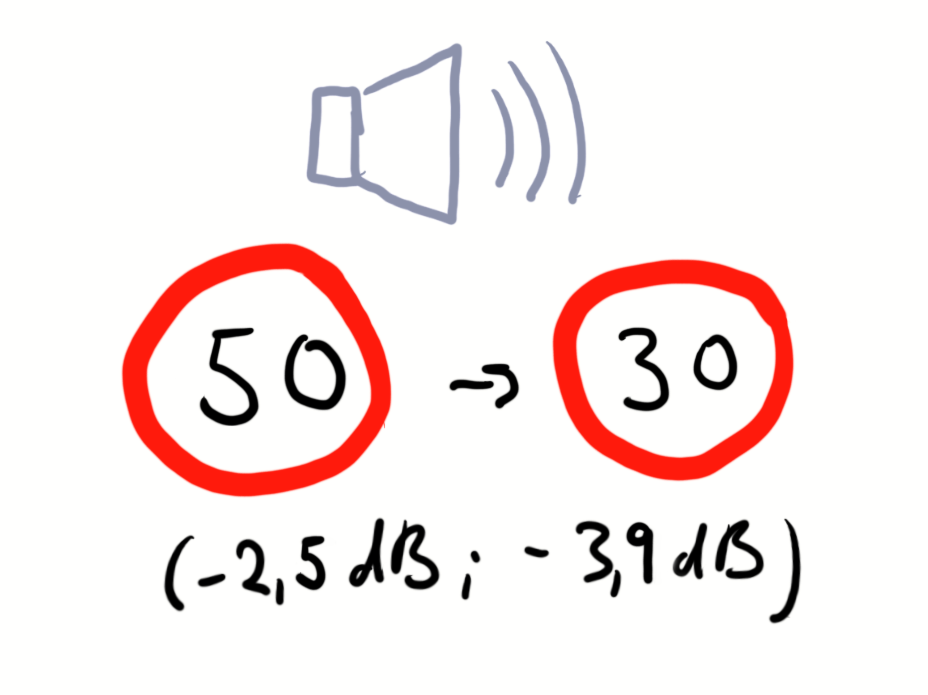

30: I’m sure they should. I make it easier for them to cross the street, they feel safer on narrow sidewalks, so I definitely help them move safely. Moreover, a collision with a vehicle at 30 km/h has similar consequences to falling from the first floor. At 50 it’s like falling from the third floor and at 70 it’s like falling from the sixth floor. Clearly, I’m bringing less serious consequences. Lower speeds also make cars make less noise, which makes being on the streets more pleasant for pedestrians, but this advantage is slowly disappearing with the advent of electric mobility.

Veronika: You mention the noise, does your introduction really always lead to lower speeds?

30: Yes, there is a reduction in noise when the speed is reduced. The level of noise can vary depending on, for example, the gradient and the gradient, or whether the road is tarmac or cobbled. But there is always a reduction of about half.

Veronika: And what about traffic pollution?

30: Here the answer is not so clear. There is a huge impact from the constant traffic, and this has a huge impact on how the city looks. How hilly it is, how high the buildings are and how wide the streets are. As for the actual production of pollutants by individual cars, that can be exacerbated by my presence, a lot depends on the individual vehicles. So I generally only have an indirect effect on emissions, when some people swap their car for a bike or walk because it makes them feel safer.

Veronika: Which cities are most keen to have you implemented on a citywide basis?

30: That’s different. Recently, there has been a lot written about cities like Brussels, Paris, or Madrid. But I’ve been in some cities for a much longer period of time in a similar scope, like Bilbao, Helsinki, or Graz, Austria, where I was introduced on a widespread basis in 1992. But even in cities with flat 30, I am not everywhere, as is often presented. In Brussels they already had confusion about where the speed was. There were lots of different residential zones and thirty zones mixed in with streets outside the zones. Nobody really knew how fast they could go where. So they took it from the ground up and picked the main thoroughfares. They even increased the limit on some of the arterials! And they put the speed limit at 30 all around, leaving the residential zones where traffic is mixed. It’s still early in terms of evaluating the statistics, but it looks pretty clear. Fewer fatalities and serious injuries and an overall improvement in the atmosphere of the city.

Veronika: Yes, that’s what I heard from my colleagues at ETSC shortly after the new limits were introduced, that the city no longer gives such a rushed impression and is generally quieter. I’m deliberately avoiding terms like calmed, which could be confusing as there have been no physical changes – well, except for the removal of a bunch of signs.

30: Exactly, simplifying intersection design, reducing the number of signs for different zones, etc. also makes city administration easier and establishes uniform rules everywhere. It may take a while for people to get used to it, but everyone will appreciate the result.

Veronika: It is sometimes speculated that your widespread introduction also leads to a slowdown in public transport and timetables have to be adjusted, there are higher requirements for driver numbers because of you, etc. What is your opinion?

30: Sometimes this can be the case, but only on the peripheral parts of the lines. In fact, in city centres there are often already different zones where the speed is reduced. So my blanket introduction will not affect the centres too much. In addition, trams and trolleybuses are subject to different regulations; they are rail vehicles. Of course there are places where they mix with cars, but the frequency of stops and intersections has a much greater effect on travel speed than the speed limit. And where there are really lots of cars, there are often dedicated lanes for public transport vehicles so that they are not blocked by traffic. Which of course allows for different speed limits. And one last thing – even where there is a flat 30, the speeds are higher on major routes.

Veronika: You’ve already nibbled on security twice, first by comparing it to falling out of a window, then with some information from Brussels. What do you think you’re really contributing to safety, it’s probably not just reducing the consequences of a crash.

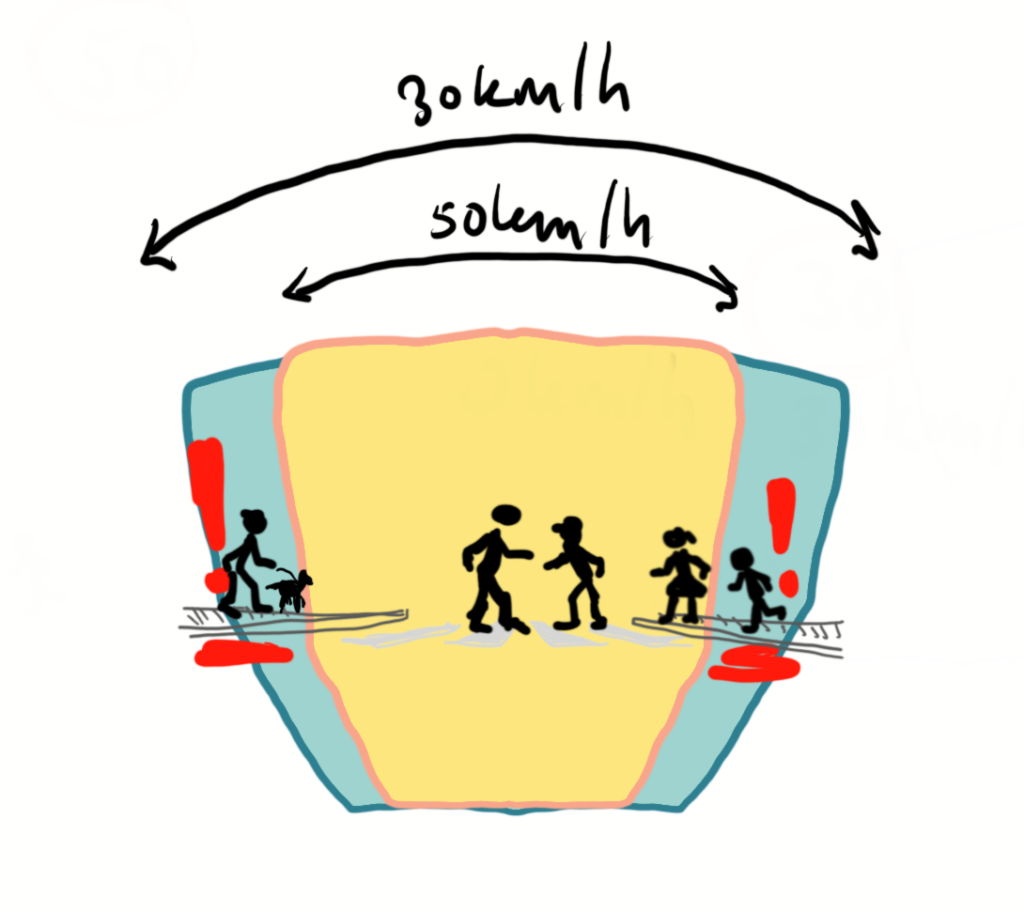

30: I’m sure not, a lot of accidents won’t happen because of me. You people’s brains can only process so much information you can see. The faster you go, the harder it is for you to keep your attention and your field of vision narrows. Objects, other people, bicycles and cars that you perceive and are able to react to at 30 may not register at all at higher speeds. And if you don’t perceive them, you are unable to react in time and an accident occurs. Then there’s another thing. If you’re going 30 and you have to brake in an emergency, you only need something like 13 metres to stop. At 50, you don’t even start braking at that distance.

Veronika: We have a really high number of accidents. And we are not alone in this, as vulnerable users (pedestrians, cyclists, motorcyclists) are a priority group for attention in improving safety at European level. You know that in the Czech Republic, there were over 64 000 traffic accidents in our municipality last year, 130 people died, and that was even a historic low, ten years ago, a hundred more people died. In addition, 955 people were seriously injured, many of whom may have permanent consequences, and almost 13 000 others suffered minor injuries? Does that mean that about one in five accidents investigated by the police in the community resulted in someone being injured or killed? In municipalities with extended jurisdiction, the GCP index shows a 12.6% share of the total number of accidents, but in terms of consequences, 63.8% of those killed and even 85.4% of those injured in these accidents are vulnerable users.

30: Those are terrible numbers, a lot of those accidents could certainly be prevented by reducing speed, although even I can’t solve everything, like drivers under the influence of alcohol or drugs who are capable of driving onto a sidewalk or a bus stop. Clearly if I were to widen more, there would be a drop in speed, even if it wasn’t to thirty, but maybe thirty-five or forty. After all, today the limit is also generally 50 and most of you are going about 56 kph on it. But even so, I’m sure it would result in lives saved and fewer injuries.

Veronika: Do you have anything else you’d like to say to my blog readers?

30: Don’t be afraid of me, but don’t put all your hopes in me either. Transport is an incredibly complex system and I’m a great complement to infrastructure improvements and non-motorised transport. It’s also been proven that just putting up a speed limit sign doesn’t solve anything if people don’t understand why. I need to talk to people and explain, showing the specific impact I will have on traffic models and visualizations. If people don’t understand my introduction, then a police check on my introduction will be necessary. Otherwise people will not follow me.

Veronika: Thank you for the interview and my fingers are crossed that you can expand more. My colleagues and I have high hopes for you, for example Prof. Yannis, who is one of the leading figures in road safety research in Europe, has made a public commitment to run 30 marathons in 30 months because of you. And I believe he can do it.

30: Wow, that’s amazing. Thanks for the invite and for the support, I know you’re trying to explain my reasoning too. See you again.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version).